Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has boosted the already high prices of oil and gas in the European Union. How come the energy situation in the EU is so dependent on Russia? What are the prognoses for energy costs and related costs of living for the near future? In Talking Economics, Katarína Stehlíková chats with Silvester van Koten, a CERGE-EI PhD in Economics alumnus, about War on Ukraine’s effect on European energy. Continue reading Silvester van Koten: We Need to Address the Shortage of Oil and Gas

Tag Archives: Economics

Meet Our Alumni: My current research investigates behavior of firms during epidemic, says Vahagn Jerbashian

Vahagn Jerbashian, our graduate on the PhD in Economics program, has been working as an Assistant Professor at the University of Barcelona since 2013. In this interview, he shares his journey from theoretical mathematics to economics, his current research interests that lie in technological change and innovation, competition, human capital accumulation, and economic growth; and his activities for the Armenian Economic Association.

What’s a Good Teacher Worth? A CERGE-EI Public Lecture by Eric Hanushek

“Economic growth is a function of education, period.” During his public lecture at CERGE-EI, Professor Eric Hanushek emphasized the enormous impact that human capital (i.e. education) has on long-term economic development. A renowned scholar in educational research, Professor Hanushek (Stanford University) used this link between education and development to make a compelling argument for improving the quality of instructors.

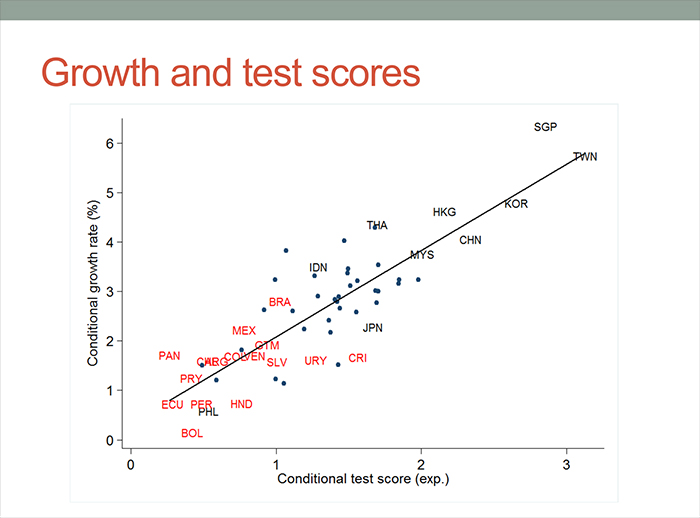

Prof. Hanushek began his lecture from a distance and gradually brought the audience ‘closer to earth.’ From the furthest vantage point, he established the unambiguous link between economic growth and test scores (i.e. what students know). A graph plotting test scores and economic growth revealed a nearly perfect correlation for a wide sample of countries over the past five decades. To Prof. Hanushek, the data screams loud and clear that imparting knowledge and skills through the educational system is the most potent means by which countries successfully grow.

Unfortunately, raising test scores is not so simple. Students may be required to attend school, and governments spend a great deal to make this happen, but merely sitting in a classroom with a teacher is not enough to guarantee meaningful learning. The question, then, is how to ensure that students learn while they sit in those classrooms.

According to Prof. Hanushek, research on student achievement has identified that good teachers play the essential role. In economic terms, how much can a good teacher contribute to economic growth? He showed that a top teacher with a class of 30 students will boost the cumulative lifetime income of that classroom group by over $800,000. Of course the inverse of this relationship also exists: lousy instruction from the worst teachers will damage their students’ earnings by a similar magnitude.

Removing the worst teachers and replacing them with average ones could contribute to large gains in test scores—and as Hanushek already demonstrated, higher test scores should directly contribute to long-term economic growth. Analyzing the Czech Republic and making conservative assumptions about teacher quality, he showed that removing the bottom 5% of teachers and replacing them with average instructors could lift the country’s test scores to the level of Finland. This in turn would add 110 trillion euros to the Czech Republic’s GDP over the next 80 years (in present value worth).

Considering the enormous impact that good teachers can have on student achievement and economic growth, the focus on improving teacher quality should be paramount. Unfortunately, solutions to improve teacher quality are often misguided and ineffective.

Rather than focus on a teacher’s educational credentials, experience, or training, Prof. Hanushek proposed solutions that work with incentives and focus on outcomes. He suggested methodically measuring testing outcomes and rewarding teachers for achieving defined objectives. He was also dismissive of those who see technology as a silver bullet. Accountability and performance rewards can be far more effective than giving students iPads.

Check out the full lecture below:

Man Bites Dog – An Interview with Dr. Kristoffer Nimark

A dog bites a man… no one cares. But how about a man biting a dog? That’s news. Dr. Kristoffer Nimark explores economic events that make news, and how media focus can exacerbate the impact of those events. Dr. Nimark lectured at CERGE-EI this fall about his research, and also sat down for a brief interview. Check it out:

Why did you choose to become an economist?

Why did you choose to become an economist?

I started to become interested in economics in the 90s. When I was in high school we had a big economic crisis in Sweden, not unlike the crisis we have now in Spain. And I saw the public debate where people had differing views that were irreconcilable with each other. I wanted to learn economics so I could understand it myself and see which arguments were valid. So I started my undergrad studies in Sweden and later I continued with my PhD at the EUI (The European University Institute) in Florence.

What is your current research?

Mostly my research is about methodological issues about how to model economies where individual agents know different things about things that all the agents care about. So you can think about how a lot of economic decisions depend on the actions of other agents in an economy. For example, if you’re a firm that wants to invest, you would like to know how much your competitors are investing; or if you’re a trader in the stock market or bond market you might be interested in knowing what other traders are willing to pay for a bond at the next trading opportunity.

Once agents have different information, predicting other peoples’ actions becomes more difficult, because you don’t know the same things anymore. And I’m trying to solve these models on how to predict the actions of others. I may want to predict the actions that other agents are taking, and they are trying to predict the actions that I am taking. And since their actions will depend on their expectations of my actions, I need to form predictions about their predictions of my expectations. So we run into methodological issues and try to understand how to solve these dilemma models.

In the paper you presented at CERGE-EI (‘Man-Bites-Dog Business Cycles’) you proposed some information structures which are different from the existing literature on ‘rational inattention.’ Can you tell us about it?

So my paper “Man-Bites-Dog Business Cycles” features one specific feature of news media: unusual events are considered more ‘newsworthy’ than more common events. The title of the paper refers to how when a dog bites a man it is normal, but it is unusual when a man bites a dog. It is only the latter event that will make news.

In the context of the paper, this means that when you have unusual macroeconomic developments like a crisis or a boom, the mainstream media is more likely to focus on the economy. Since the news media is more likely to focus on the economy when we have a recession or a boom, it influences the business cycle. In particular, I show that this intense media focus can exacerbate things—you get stronger booms and recessions than you would otherwise.

Very interesting. What are your main conclusions?

My main finding is that the economy appears to respond strongly to shocks that don’t seem large enough to really justify the types of crises we observe. The model shows how we have sometimes extremely strong responses to only small changes in fundamentals. So even if there is only a small change in productivity, you have a very large change in output, and vice-versa. And this can be partly explained by the intense media focus.

So in this sense, the media focus on the economy is a bad thing?

I don’t show in the paper that this is suboptimal. It’s still possible that this media response is good, that a strong response is appropriate. I don’t really discuss this.

We students are making decisions about our topics for our PhD thesis. Where is the gap in economic research today?

You shouldn’t think too much about it. When you choose a topic as a PhD student you should choose something that you find interesting enough to work on—something you are willing to spend 60-70 hours a week on it for three years. Some people find it’s interesting to work on new things and they’ve identified some gaps in economic thinking they think are important. And I think that’s great, and that’s often very good research. But you shouldn’t artificially look for gaps, especially if you don’t find it interesting—and you won’t be able to convince other people that it’s interesting!

The most important thing is to work on something you find interesting yourself. Most people don’t think it’s interesting to repeat other people’s work, so in one sense it always means plugging some gap somewhere.

Dr. Nimark is a researcher at CREI (Centre de Recerca en Economia Internacional), adjunct professor at Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and affiliated professor at Barcelona GSE.

Read the paper Man-Bites-Dog Business Cycles

Interviewer: Sophio Khozrevanidze, 2nd Year PhD Student

Friday, 5 October 2012

Nobel Pursuits: CERGE-EI Interviews Nobel Prize Winner Christopher Sims

Christopher Sims won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2011. When he came to CERGE-EI this summer to lecture about his research, we knew we had to sit down with Professor Sims for a more intimate interview. Take a look at the conversation between this brilliant laureate and some of our PhD students at CERGE-EI:

What can you tell us about the journey to winning the Nobel Prize? Where you got your ideas, who influenced you the most, the evolution of the research?

My Nobel Prize is focused on the empirical econometric work I did on monetary policy. My ‘Noble lecture’ kind of goes through that, but I can summarize it: In the 1950s and early 1960s, Keynesian Economics was dominant. And in the 50s, which was very close to the Great Depression, the Keynesian consensus was that monetary policy was not very important and fiscal policy was. And this was a legacy of the period of the Liquidity Trap in the 1930s, when monetary policy indeed was not very effective—a period much like the present, in that respect.

Back then, econometricians developed large statistical models, based on Keysian Theory. They built on the insights of Trygve Haavelmo and Jan Tinbergen, two earlier Nobel Prize winners. And they ended up with very large unwieldy models, for which the statistical methods proposed by Haavelmo didn’t really work very well.

So into this scene came the monetarists led by Milton Friedman, and they used much simpler statistical models and focused on just a few variables. They argued that the connection between the money stock and income was the central, most important fact in macroeconomics. But this factor didn’t emerge as central and important from the perspective of those big Keynesian models.

So into this scene came the monetarists led by Milton Friedman, and they used much simpler statistical models and focused on just a few variables. They argued that the connection between the money stock and income was the central, most important fact in macroeconomics. But this factor didn’t emerge as central and important from the perspective of those big Keynesian models.

There was really no way for these two schools to resolve their differences with the econometric methods that were available at the time. But in the big Keynesian models, everyone knew they made assumptions that weren’t believable.

So what I did was first I validated the monetarists. They were running regressions of nominal GDP on current and past money stock, and interpreting them as policy-exploitable relationships. They interpreted them as if changing the money stock would change nominal GDP according to the coefficients they estimated in those models. I argued that if that were true, there was a testable implication. This was a causal model. In this logic, future money should not be correlated with income, given past money. So I checked that implication and it turned out that the implication was satisfied by the data.

And so something that both Keynesians and I would have predicted would show that the monetarists were wrong, actually showed they were probably right.

But then a student of mine, Yash Mehra, did a study of so-called ‘Money Demand Equations’. Because at the same time that Friedman was estimating these income-on-money regressions, other people were putting money on the left side and income and interest rates on the right. They were calling this ‘money demand’, and it was another similar equation regression. So I said to Mehra: ‘this looks like a good thing to check, because If money is causing income, than these money demand equations must be nonsense. Money doesn’t belong on the left-hand side.’

But Mahra did the tests and it turned out they passed. He showed that with money on the left and income and interest rates on the right, it looked like everything on the right-hand side satisfied this condition that the future size of the variables shouldn’t matter.

I was puzzled by these results and decided that I wasn’t going to make sense of them unless I put together a model with more than one equation. So I estimated a small, vector regression with several equations, and once I did that I could see that interest rates predict money, and if that’s right, then the usual ‘monetarist’ interpretation of this system didn’t really hold up.

So there is a kind of consensus now on how the economy dynamically responds to monetary expansion or tightening. It’s not really precise, but GDP tends to respond a little quicker than prices, and they both tend to go down when money is tightened. These come right out of quantitative statistical estimates, and there are different ways to do the identification, to separate these two influences. And they give consistent results. That was what the prize was for, that sequence of developments.

Continue reading Nobel Pursuits: CERGE-EI Interviews Nobel Prize Winner Christopher Sims

The Economics of Voting with Professor Dirk Engelmann

Professor Dirk Engelmann was back at CERGE-EI; this time to share his latest research on the intriguing behavioral science of voting. Now a Professor at the University of Mannheim and Director of the Experimental Economics Laboratory, Engelmann was a Reader and Professor of Economics at Royal Holloway, University of London and an Assistant Professor here at CERGE-EI before limiting that role to a senior researcher. He is currently a member of the editorial board of the American Economic Review, associate editor of The Economic Journal and co-editor of the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization.

Professor Dirk Engelmann was back at CERGE-EI; this time to share his latest research on the intriguing behavioral science of voting. Now a Professor at the University of Mannheim and Director of the Experimental Economics Laboratory, Engelmann was a Reader and Professor of Economics at Royal Holloway, University of London and an Assistant Professor here at CERGE-EI before limiting that role to a senior researcher. He is currently a member of the editorial board of the American Economic Review, associate editor of The Economic Journal and co-editor of the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization.

Knowing his academic and research competence first hand, the CERGE-EI community was eager to listen to his insightful lecture on a very interesting area. And they were rewarded with a fascinating talk on how to model the efficiency aspects of democracy, elections, and majority voting. The seminar was entitled “Choosing How to Choose: Efficiency Concerns and Constitutional Choice”, and it was based on an experimental study of group decision-making to document the (in)efficiency of majority voting.

Continue reading The Economics of Voting with Professor Dirk Engelmann

The Path To Success

Would you like to achieve greater success in your career? There is no universal recipe how to do so, but here I take the opportunity to present the story of one of our professors, who has recently become a Member of the Bank Board of the Czech National Bank. He has been Citigroup Endowment Associate Professor at CERGE-EI receiving tenure in 2004, and also served as a Director of CERGE-EI. He is the author of 20 articles, 25 books and chapters in books, 30 working and discussion papers and many publications in popular press. He is also the holder of a significant number of grants and tenders. Do you know who is he? Professor Lubomir (Mirek) Lizal. Being impressed by his spectacular career progress, I decided to investigate how Lubomir achieved his success.

Would you like to achieve greater success in your career? There is no universal recipe how to do so, but here I take the opportunity to present the story of one of our professors, who has recently become a Member of the Bank Board of the Czech National Bank. He has been Citigroup Endowment Associate Professor at CERGE-EI receiving tenure in 2004, and also served as a Director of CERGE-EI. He is the author of 20 articles, 25 books and chapters in books, 30 working and discussion papers and many publications in popular press. He is also the holder of a significant number of grants and tenders. Do you know who is he? Professor Lubomir (Mirek) Lizal. Being impressed by his spectacular career progress, I decided to investigate how Lubomir achieved his success.

Continue reading The Path To Success