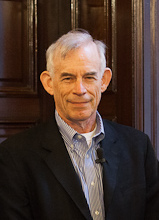

Dr. Ferre de Graeve, a researcher at Sveriges Riksban (Sweden’s central bank), visited CERGE-EI back in November to discuss fiscal policy in contemporary DSGE models. Check out the hitherto unpublished interview between Dr. de Graeve and CERGE-EI PhD student Liyou G. Borga

Why did you choose to study economics? What motivates you?

At the age of 18, going out of school, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I decided to study but I pretty much eliminated subject after subject, and what was left was economics. After about three or four months of studying economics, I knew I wanted to do research in the field. And here I am. No regrets so far.

How do you approach your research interests?

I tend to not take advantage of economies of scale. I switch topics a lot. And that’s essentially because I want to learn more. Certainly there are disadvantages to that. But it’s so easy to get excited by something entirely new. I just pursue ideas that I find interesting.

At any point in time I have a couple ideas that I don’t pursue but I think about. But if let’s say a year later they’re still in my head, chances are I start working on them.

What are you working on now?

Essentially I am presenting at CERGE-EI an old paper of mine in which we were concerned with the term structure of interest rates. Now I am revamping that paper from a different angle. There has been a lot of discussion lately about fiscal policies, for obvious reasons. What we realized is that, although the paper has nothing to do with fiscal policy, essentially it turns out to be quite informative about what people call ‘fiscal inflation’. This is the probability that inflation is going to be driven by fiscal policy in the near future. So we basically estimated the model, and it turns out that the model immediately speaks to this issue. It was only two weeks of research, and all the results are already there. That’s definitely not my usual experience.

How did that happen? Is it just that you got lucky? Why did you decide to go back and look?

In terms of work, we got lucky, because we didn’t have to do much. There are a couple of people these days who warn us about fiscal inflation, and perhaps it’s the sense in their arguments that made us go back and look.

One big area for our students is macro models. This DSGE model comes up often in macro issues. Can you tell us in laymen-terms what this model is and why it is different from traditional models?

DSGE models are essentially models that describe business cycle fluctuations and are built from what we call “micro foundations”; deep structural parameters that determine economic agents’ behavior.

Let me distinguish DSGE models from reduced form forecasting models on the one hand, and old-style structural models on the other. DSGE models complement both. Regarding the first set of models, the important part is that the DSGE models allow us to understand something that the forecasting models don’t necessarily do. Both models will produce forecasts. But DSGE models build on mechanisms that have an economic interpretation. The big advantage that implies for example for central banks is that they allow storytelling. You can think about policies and how they will work. You can create forecasts conditional on policies and that’s a lot harder to do in traditional reduced-form models.

The old-style structural models had the same objective as DSGE models. However, the way they were constructed was rather ad hoc, often inconsistent with theoretical models. They therefore produced answers to policy questions that were hard to put faith in.

How risky is it for central banks to adopt this model and base their forecasts on it, if we base our micro-foundations on some assumptions that don’t work?

I think the main risk is over-estimating the value of a model. I mean as soon as you have a model that you can use to tell stories, you may have too much attention for that model and you may stop thinking about model uncertainty. Because there are other models out there we are not studying. The current crisis is hopefully teaching us that we should think about other models too. In building a model and using it for policy analysis, there are a lot of steps we take that involve assumptions that won’t do well in the current state. We often fail to generate crises in these models of the type we see in reality. That said, I think there is a lot of value in being able to communicate clearly through a model. I definitely think there is value in DSGE models and how they are constructed, but we shouldn’t think that we’ve solved everything here.

As students, we always want to know advice about how to pursue research. Do you have any advice?

I ask myself that question everyday, and I don’t know. The most important factor, I think is this: pursue your interest. In research you never know where you’re going to end up. You’ll always find out that things don’t work out. So you better have inherent motivation to get you going, even when you face those stages of research.

If it’s your interest, you’re kind of blessed to have the opportunity. For me, it’s certainly better than a lot of alternatives. The fact that I can think of something I find interesting and follow up on it—the average job doesn’t necessarily give you that.

Following the literature might give you more of a probability of getting publication success, but maybe there is value in thinking completely differently and pursuing it.

What is economics now, in terms of importance and relevance, compared to the past?

Well the field is getting so big now. When I started, I had the impression that everyone was doing macro and everyone was discussing with everyone. Now it seems there are so many fields, and they have all developed so much, so it’s hard to know about everything.

So is that a good thing?

Perhaps with more fields we are inclined to go deep in every particular field, but then you can easily lose track of the bigger picture. It’s important that at least some people keep a bird’s eye view of all the fields, and question whether we are focusing on the right questions. Of course sometimes reality does it for us, such as with this recent crisis. Afterwards, a lot of researchers I know thought ‘am I working on the right topic, given that current events are so massively important?’. Of course having many different fields can help people learn from each other and build.

Economics is indeed very diversified now, but there are some important questions unanswered. What research questions should be best pursued today by students?

Although we have models that have evolved to understand crises, we’re not there yet. I’m sure there are a lot of questions that are unanswered relating to all aspects of the financial crisis: both what’s happening in the financial sector, how it related to what’s happening in the real economy, and feedback between the two. There are a lot of things we don’t know in this area.

Mostly our students are from transition and developing countries. In terms of research, what is the comparative advantage of a student coming from one of these countries?

Well for one thing, they probably have more observations and experiences with crises than Western Europeans have. I see that roots are important in research. But having had a good education will basically allow you to do anything. So then it comes back to interest. I don’t necessarily see a comparative advantage, it’s just that there is some correlation about what you think is important and where you come from. But given a good education, you’re basically going to be able to do whatever you want, because you have a wide understanding of issues and the ability to learn.

Author: Liyousew G. Borga, 2nd Year PhD Student

9 November 2012