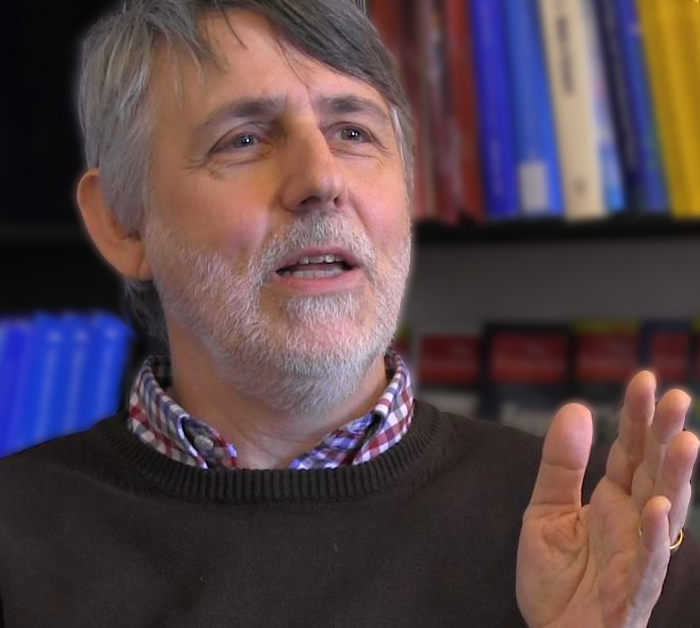

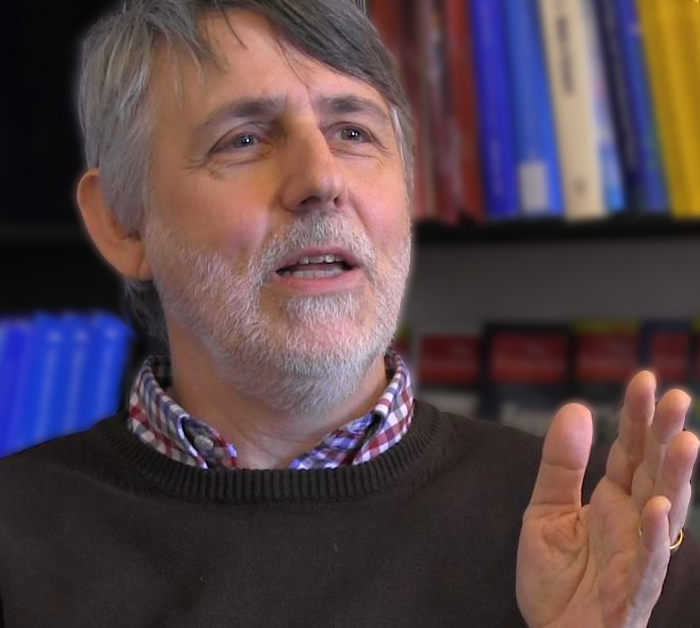

Professor Marcel Fafchamps (Oxford University) researches development economics, with a particular interest in social networks, risk-coping strategies, and market institutions. With advanced degrees in law and economics, Professor Fafchamps is fascinated by the role of institutions (both formal and informal) in the development of productive economic exchange. His recent papers include work on markets, political economy, social networks, and link formation. He also serves as deputy director for the Center for the Study of African Economies.

Professor Fafchamps visited CERGE-EI recently to present a paper titled “Networks and Manufacturing Firms in Africa”. While here, he sat down for an interesting interview with two CERGE-EI PhD students, Liyou G. Borga and Dejan Kovac.

————————————————————————————————-

Before you began doing economic research, you did some development work. Why did you choose to go back and get your PhD?

That’s correct. After completing my military service I went to work for the ILO in Ethiopia. I initially went for a year but ended up staying for four and a half years, and I even met my wife there. I became interested in research at that point, and I noticed that everyone around me who was doing interesting research already had a PhD… so I thought, I better get one of those!

You work on research and you design some policy recommendations for developing countries, but these countries and their government are not always fond of these recommendations and may not put them in to practice. Is it frustrating to do this kind of work?

I find it very rewarding. Even though I started in policy, over time I moved away from pure policy-oriented work and more into behavioral work, because I think that if you can understand some of the main drivers of human behavior, you can try to anticipate how they will respond to various policies, even policies we haven’t tested yet. That’s always been my personal approach.

So I don’t try to come to the government of Ghana and say ‘You should do X’. I never could see myself in that role. For several reasons: One is that I don’t think I should be advising the government of Ghana. I don’t know enough about Ghana. They should be listening to their own people, they should have their own local capacity. I train people from a whole series of developing countries, and a lot of them go back to their country. So I try to give them the best possible grounding and training. In my view teaching is my most important policy work.

And the second is that politicians are on a different clock than we are. They are subject to pressure; they deal with crises and emergencies all the time. If the prime minister wants me to advise on what to do, they want an answer now. But research takes time—it will take at least two years before you get a meaningful result. Politicians never have time to wait that long.

And the third thing is that policy research is impossible in the following sense: You can never do research on something that has not happened yet. Hence you cannot give a definitive answer to someone who wants to know the future effect a proposed policy. You can offer a prediction based on your understanding of the processes at work, and hopefully this opinion is an informed one so you can give a better prediction than other people. But at the end of the day it’s only a prediction. The politician should blend this prediction to their own predictions based on their own understanding of the various political dynamics at work, which they understand way better than you ever will. And of course, as a policy advisor I am not really responsible for my actions as an advisor. I can say ‘well you should do X, Y, and Z’— and then what? What if it costs millions, or kills people? I think they should be the ones who make the decisions, not outsiders who are ultimately not responsible for the consequences of their advice.

You are involved in the Center for the Study of African Economics. Do you see a reason to be an optimist about African development? Are they on the right track?

You know the answer to that question is yes. There will be hiccups along the way, just like in Latin America (and if you want to find a part of the world that is most comparable, in terms of population pressure, types of resources, geographical location, and to some extent history, it’s Latin America). The way I see it, the main historical difference between Latin America and Africa is the pattern of colonization and pattern of settlement. America was colonized very early, from 1500 onward, and ended in the 1820s, roughly. And because the Europeans brought many diseases which the Native Americans were not immune to, there was a very large depopulation on the continent. So you have a lot of Latin American countries where big native populations were largely marginalized, and only now are they politically emerging after 200 years of independence.

That’s very different in Africa where it was the opposite. The settlers didn’t survive very well, and the native Africans were much better at surviving, so colonization started very late and lasted for a very short period of time. And it did not, except in South Africa, generate a settler population. Whatever settler population was introduced as a result of colonization, a lot of them have left.

So then if you compare Latin America to Africa, you see that these settlers bring with them a lot of talent and human capital. They bring familiarity with business practices, with modes of contracting, and these get transplanted nearly immediately. You don’t have to wait for the local population to learn how to take advantage of innovations like supplier credit, banking, etc.

This explains why it took longer in Africa. But now it’s happening ! I’m very optimistic. There’s no reason why it shouldn’t continue. It could have happened faster if there were more settlers, but then you would have the same problem we see in Latin America, where the native population gets side-lined. In Africa that is not taking place.

So in a sense, in a bizarre way, I am more optimistic for Africa; it was a bit harder to get started because there was a lot of learning to do about modern business practices and institutions, but once they have learned it, they’ll be in charge.

A lot of your research is based on Social Capital. So what is social capital, and how does it influence economic outcomes?

The way I think of social capital, the way the word is useful, is that it’s a flag behind a research agenda which looks at certain phenomena. There are three components: norms, networks, and outcomes (for example, the provision of public goods).

It’s funny that sometimes researchers will only look at the first and the third. For example, they look at certain types of social norms and how they influence outcomes, but do not focus on the networks, or do not even require network dimensions. Other researchers focus on networks and outcomes, but not on the norms. So in the first case, social capital will be the norms people have internalized, and in the second case social capital will be their networks, for example how many friends they have, what kind of friends they have. In this sense it is a strange research agenda, because it doesn’t always use this phrase with the same meaning.

I think the provision of local public goods is absolutely essential for communities, and also for business communities. And this is what has particularly interested me. Because you don’t get very effective business communities without them using up-to-date organization forms and contractual forms between themselves. When you think about growth and development, if you try to explain the last two hundred years and the rapid increase in standards of living across much of the world, what you see is the spread of innovation. If you learn something about knowledge in one particular area it can spread and help you innovate in another area. But the innovations people typically focus on are things, like the steam engine or electrical power, or consumer goods like the computer and the telephone. But they forget about institutions and forms of organization. Yet that’s what we economists do. This is the kind of thing we study and where we offer innovations. For example: independent central banks, auction for cellphone airwaves, conditional cash transfers. We offer research on innovations in organizational forms and institutions.

But the thing is: if we discover that a computer is useful, you buy a computer. However, if you discover that trade credit is useful, it’s not so easy to introduce that on your own. Everyone is going to suck you up, take your credit, and not pay you. It has to be a collective decision. So you get into this issue: how to respect other people’s trade credit practice so it becomes like a local public good within your community. But how do you generate that? That’s pretty interesting. It involves social norms, respect for social norms, it involves networking, coordination. Basically it involves the provision of local public goods.

What do you think of bonding capital becoming a negative influence, for example the Mafia in Southern Italy? Is this type of thing possible to empirically investigate?

I think this point has been made before. I would say it’s worse than that, in the following sense: if you tell me that people with a bigger interpersonal network derive advantages from it (e.g. getting a job, doing more business, easier access to credit, ability to deliver public goods within their group), then by definition you are saying there are other people out there who don’t have these benefits. So I would say that every time that interpersonal social capital is helpful, it is also creating inequality. For that reason, I am very skeptical of interpersonal social capital, and why I prefer generalized trust and generalized norms; I prefer things that are the same for everyone and don’t exclude anyone.

So this research can be applied quite generally?

So this research can be applied quite generally?